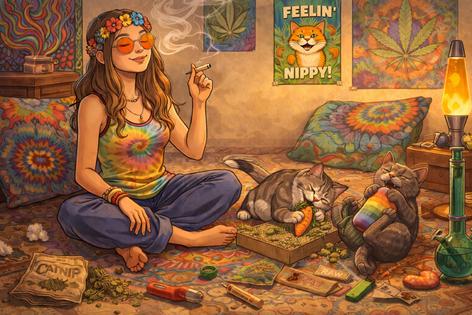

If You Don’t Tell Your Cats About Nip, Who Will?

Published in Cats & Dogs News

Somewhere between the crinkle of a paper bag and the hum of the vacuum cleaner lives one of the great domestic mysteries: catnip. It arrives quietly, usually in a small plastic pouch or sewn into a mouse-shaped toy, and within seconds transforms a dignified predator into a rolling, drooling philosopher. The cat flops. The cat chirps. The cat stares into the middle distance as if contemplating the universe or, possibly, the couch leg.

To human observers, the scene feels familiar. Not identical, not interchangeable—but familiar enough to invite comparison. Catnip does to cats what marijuana is often said to do to people: relax them, excite them, confuse them, and occasionally inspire behavior best described as “deeply personal.”

The analogy has limits, and science insists we respect them. Still, the resemblance is too culturally rich to ignore.

The Plant, the Myth, and the Smell

Catnip, or *Nepeta cataria*, is a member of the mint family. It grows easily, smells faintly herbal, and contains a compound called nepetalactone. That compound binds to receptors in a cat’s nose and triggers a response that looks a lot like pleasure, playfulness, or mild existential wonder.

Marijuana, for humans, involves a different plant, different chemistry, and a different nervous system. The comparison ends at effect, not mechanism. Catnip is smelled, not eaten, and it does not act on the feline brain the way THC acts on the human one. Veterinarians and researchers are very clear on this point, and they are correct to be.

And yet. The behaviors that follow—relaxation, silliness, sudden affection, intense focus on nothing in particular—feel culturally parallel. The plant does not intoxicate cats in a clinical sense, but it does alter their behavior temporarily in a way that humans instantly recognize.

Who It Works On—and Who It Doesn’t

Not all cats respond to catnip. Roughly half to two-thirds do, depending on the study. Sensitivity is inherited, meaning some cats are simply immune. They sniff the toy, blink once, and walk away as if offended by the suggestion.

This, too, mirrors human experience. Not everyone enjoys marijuana. Some people feel relaxed; others feel anxious, sleepy, chatty, or deeply uninterested. The variability does not negate the phenomenon—it defines it.

Age also matters. Kittens generally do not respond to catnip until they are several months old. Senior cats may react less intensely. The effect tends to peak in adulthood, when curiosity, confidence, and coordination briefly align. Afterward, tolerance sets in. A cat exposed to catnip too frequently may stop reacting for a while, much as humans can become habituated to repeated stimuli.

The Behavioral Shift

When catnip works, it works fast. Within seconds of exposure, cats may roll, rub their faces, paw the air, vocalize, sprint, freeze, or collapse into blissed-out stillness. The episode usually lasts five to fifteen minutes, after which the cat loses interest and may appear mildly embarrassed by its own behavior.

Humans watching this often project. The cat looks happy. Or relaxed. Or “stoned.” The temptation to narrate is strong. The cat seems to have entered a private mental space, temporarily detached from the usual concerns of food bowls and territorial disputes.

This projection says as much about humans as it does about cats. We recognize altered states because we have them. We understand the appeal of stepping sideways out of routine, even briefly. When a cat experiences something that looks like joy without purpose, it resonates.

No Addiction, No Hangover, No Moral Panic

Here the comparison becomes reassuringly boring. Catnip is not addictive. Cats do not seek it compulsively. They do not suffer withdrawal. They do not neglect their responsibilities or sell household objects to fund their next hit of dried leaves.

The effect wears off on its own, and cats typically show no interest again for hours or days. If anything, they are models of moderation. When the moment passes, they nap.

This is where the analogy with marijuana often becomes cultural rather than chemical. Human societies have spent decades debating the moral implications of altered states, often projecting fear onto substances rather than behavior. Cats, blissfully unaware of moral panics, simply enjoy their moment and move on.

The Ethics of Disclosure

Which raises the playful but pointed question: if you don’t tell your cats about catnip, who will?

Many cats live their entire lives without encountering it. They nap, hunt toys, judge their humans, and never once experience the peculiar joy of rolling face-first into a sock infused with dried mint. Is that a deprivation? Or just a neutral absence?

There is no obligation, of course. Cats are not missing something they cannot imagine. Still, humans routinely enrich their pets’ lives with stimulation—new toys, window perches, puzzle feeders. Catnip fits comfortably into that category. It is optional, temporary, and widely enjoyed by those it affects.

The humor lies in the idea of secrecy. The human knows something delightful exists and chooses whether to share it. The cat, meanwhile, trusts completely. This dynamic mirrors countless human debates about access, experience, and choice, played out on a much smaller and furrier scale.

Ritual and Context

Like many altered experiences, catnip works best in context. A calm environment, a familiar space, and a safe surface make the difference between joyful play and overstimulation. Cats exposed to catnip in stressful situations may react unpredictably or not at all.

Humans understand this intuitively. Set and setting matter. The same substance can feel relaxing in one context and unpleasant in another. Cats, though unable to articulate this, demonstrate it clearly. They prefer their indulgences at home.

The Human Gaze

Perhaps the most revealing aspect of catnip is not what it does to cats, but what it does to the people watching. Humans laugh. They film. They narrate. They anthropomorphize wildly. The cat becomes a mirror for human curiosity about pleasure, control, and altered consciousness.

Watching a cat on catnip is funny because it is safe. There is no stigma, no long-term consequence, no existential dread. The cat will be fine. The human can enjoy the spectacle without worrying about outcomes. It is a rare chance to observe joy without complication.

A Gentle Conclusion

Catnip is not marijuana for cats. Science insists on that distinction, and rightly so. But the comparison persists because it captures something emotionally true. Both experiences represent a break from routine, a softening of edges, a moment where the world feels slightly different.

Cats do not ponder these moments. They live them, briefly and fully, then return to napping in sunbeams as if nothing happened. Humans, watching, project meaning and laughter and a little envy.

If you choose to introduce your cats to catnip, you are not opening a forbidden door. You are offering a small, safe novelty in a life built on repetition. If you choose not to, your cats will still be cats—curious, dignified, ridiculous.

But if you ever watch a cat discover nip for the first time, wide-eyed and blissfully unburdened, you may find yourself thinking: someone had to tell them.

========

Martin Calder is a writer covering culture, animals, and the strange overlap between human habits and nonhuman joy. His work focuses on everyday rituals, humor, and the quiet ways people relate to the creatures they live with. This article was written, in part, utilizing AI tools.

Comments