SC Rep. Clyburn's new book: history, a cautionary tale and a peaceful call to arms

Published in Books News

Most books have a story of how they came to be, and so it is with Rep. Jim Clyburn’s latest book: “The First Eight.”

Some years ago Clyburn, 85, was in his office at the U.S. Capitol when visitors pointed to portraits on his conference room wall of eight African Americans dressed on 19th century garb. Clyburn explained they were the first eight Blacks from South Carolina who had been in Congress, and they had served during the 1870s, 1880s and into the 1890s.

“One of them said to me, ‘My goodness, I thought you were the first African American from South Carolina to serve in Congress’,” said Clyburn, adding he quickly told the group he — elected in 1992 — was only the first in the 20th century. “No, no, no before I was first, there were eight.”

The encounter made up his mind: His next book would be about those eight South Carolina African American men who served in Congress in the post-Civil War era and how hardball politics and violence in the state and Washington eventually relegated Blacks to second class citizenship and Jim Crow apartheid during much of the previous century.

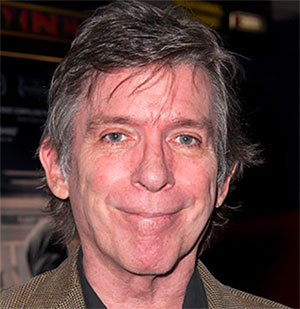

Clyburn told that story last month to a gathering of approximately 250 people at the University of South Carolina Rice Law School on a cold and rainy Saturday morning. They had turned out to hear him talk and for a signing of his book, “The First Eight: A Personal History of the Pioneering Black Congressmen Who Shaped a Nation.” He has promoted the book on national talk shows such as NPR, C-SPAN, PBS, NBC and CNN also.

Before the signing, Clyburn discussed his book with USC civil rights historian Bobby Donaldson, who called the Congressman both “a maker of history and a chronicler of history.”

USC law school dean William Hubbard told the crowd that Clyburn has been over the decades “an anchor for all that’s good in politics ... He exemplifies what I believe the Founders wanted in the people who would represent us in Congress.”

More than a history

As it turned out, Clyburn told the audience under Donaldson’s questions, he wanted the book to be “informative and educational,” shining light on the lives of South Carolina’s first eight Black congressmen — and the charged times in which they lived.

But the turmoil of the 2020 presidential election, the violent attack on the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, to stop the certification of that election, and the submission by some states of false slates of presidential electors to Congress, Clyburn realized that history was repeating itself and his book would be a “cautionary tale.”

“What happened (after the 2020 election) is exactly what happened post-Civil War that brought an end to the careers of these eight people … and kick-started the 95 years between No. 8 and yours truly, No. 9 — 95 years,” Clyburn told the crowd.

South Carolina’s last Black Congressman, George Washington Murray left office in 1897, and Clyburn was elected in 1992 — thus the 95-year gap.

A little history: Up to 1877, Union army forces were stationed in many Southern states, including South Carolina, trying to make sure the white supremacist former Confederates could not seize total power and expel Blacks from office. In South Carolina, numerous white “rifle clubs” sprang up, intimidating Blacks, killing some and keeping them from voting. The U.S. Army was sent into South Carolina, but it never quite succeeded in reining in the whites, many combat-hardened ex-Confederate soldiers.

After the bitterly contested 1876 presidential election, in which one electoral vote in the U.S. House of Representatives threw the presidency to Rutherford B. Hayes, Hayes ordered U.S. Army out of South Carolina. The army left in April 1877, and South Carolina whites began to assume control by denying Blacks the right to vote.

It was “a decision that would seal the political fate of Blacks in South Carolina for a century,” writes Clyburn in his book.

Famed historian Walter Edgar reached the same conclusion in his landmark 1998 “South Carolina: A History,” writing of South Carolina, “Those who had lost in 1865 triumphed in 1877.”

Although Edgar’s excellent 700-plus page history chronicles many aspects of Black-white relations through the decades, it gives scant mention to the eight Black members of Congress in the Reconstruction era.

What makes Clyburn tick

At age 85, when most people have slowed down, it’s not surprising Clyburn has spent the last several years writing a book about justice, history and voting rights in South Carolina.

That’s how he was brought up.

”My dad was just all about education,” Clyburn told the law school group. “Every morning before breakfast, we had to recite a Bible verse.” And before going to bed, he and his siblings had to share with their parents a current event they had gleaned from reading a newspaper (in those pre-internet days).

“‘My dad thought the greatest person in the world was Robert Smalls; my mom, she thought the greatest person was Mary McLeod Bethune.” Clyburn said. Bethune was a nationally prominent educator and civil rights activist who was born in Mayesville.

And the reader of Clyburn’s book will find inspiring quotes from The First Eight, such as one from Robert Smalls, who said, “My race needs no special defense, for the past history of them in this country proves them to be the equal of any people anywhere. All they need is an equal chance in the battle of life.”

Many stories

Clyburn tells stories of “the first eight” amid a varied backdrop over the last 50 years of the 1800s, a time that includes antebellum South Carolina, the Civil War, the sometimes bloody power struggles between Blacks and the old Confederates from 1865 to 1877 followed by the installation of white rule into the 1900s.

Here are thumbnail sketches:

•Joseph Hayne Rainey (1832-1887). First South Carolina Black to serve in the U.S. House of Representatives, from 1870 to 1879. Represented the 1st Congressional District. Born a slave on a Georgetown plantation, Rainey became a barber in Charleston, was drafted into the Confederate army and was able to escape to Bermuda. After the Civil War, he moved back to South Carolina. Congress was all white until Rainey was sworn in.

•Robert Carlos De Large (1842-1874). Served in U.S. House from 1871-1873 for the 2nd Congressional District. De Large grew up in antebellum South Carolina as the free son of free Black parents. De Large grew up in Aiken and was able to move to Charleston for an education, taking advantage of his parentage during the days of slavery.

•Robert Brown Elliott (1842-1884). Served in U.S. House from 1871-1874. 3rd Congressional District. A Northerner who was born free, Elliott arrived in South Carolina as an adult where he wrote for a newspaper, was elected to the state legislature and gained a reputation as a “brilliant political organizer” and a statesman.

•Richard Harvey Cain (1825-1887). Served the U.S. House in 1873-1875 (at-large District) and 1877-1879 (2nd District). Cain was also a Northerner who was born free and came to South Carolina as an adult.

•Alonzo Jacob Ransier (1834-1882). Served in U.S. House from 1873-1875. 2ndDistrict. Ransier grew up in antebellum South Carolina as the free son of free Black parents. He became a journalist and a political activist in Charleston politics after the Civil War.

•Robert Smalls (1839-1915).Served in U.S. House from 1875-1879 and from 1882-1883 representing the 5th District; from 1884-1887 representing the 7th District. Born a slave, Smalls became a Civil War hero for the North when he sailed a prized Confederate ship out of Charleston harbor and delivered it to Union forces. His numerous attributes and achievements — including registering Blacks to vote after the Civil War — made him the greatest of all South Carolinians, Clyburn writes.

•Thomas Ezekiel Miller (1849-1938). Served in U.S. House from 1890-1891 representing the 7th District. He was first president of what is now S.C. State University in Orangeburg. Miller was born to white parents and was raised by free Black parents in Charleston. His adoptive mother died when he was nine, and he went to work delivering newspapers (and reading them). During the Civil War, he worked on South Carolina’s railroad system while wearing a Confederate uniform.

•George Washington Murray (1853-1926). Served in U.S. House from 1893-1895 representing the 7th District; from 1896-1897 representing the 1st District. Murray won his freedom through emancipation and throughout his life, “didn’t shy away from confronting political opponents or standing up for what he believed was right,” Clyburn writes in his book.

Despite their diverse backgrounds and different experiences, each of them rose to the top of his profession and “occupied a unique place in our nation’s history” during one of its most turbulent periods: the Reconstruction Era, Clyburn writes.

Of the eight, Smalls is the favorite of Clyburn, who called him “the most consequential South Carolinian in history.”

Born a slave in Beaufort, Smalls defied slave owners characterization of Blacks as an inferior race and on a national stage during the Civil War proved “he was not on the equal of white men, but a talented leader of all men,” Clyburn writes.

Smalls not only learned to sail and engineered the difficult theft of a 147-foot Confederate steamship from heavily guarded Charleston Harbor in 1862, he also became a Union war hero who met President Abraham Lincoln in the White House and persuaded Lincoln to authorize 5,000 Black recruits into the Union Army. This first, but not the last, introduction of Black troops into the Union Army would change “the course of the war,” Clyburn writes.

Smalls was also formally made captain of the steamship he stole from the Confederates.

“It ... marked the first time he could be called Captain Smalls, a title that had never been granted a Black — enslaved or free,” Clyburn writes in his book.

In his book, Clyburn writes that, “South Carolina’s history has not always been positive. Some of it has been very unpleasant for me and many others, especially those who look like me. But our history is what it is, and I believe that complete history should be told.”

Today, Clyburn writes, the MAGA (Make America Great Again) proponents seeks to rewrite American history, but “African American history is our nation’s history. The truth remains the truth. The more we tell the stories of our past, the less effective attempts to alter them will be.”

Interview and reactions

In a brief interview before his talk, Clyburn was asked who he envisions replacing him when he leaves office — former Columbia Mayor Steve Benjamin? former state legislator Bakari Sellers?

In addition to those two African Americanbs, there are a lot of possibilities, including his daughter Jennifer Clyburn Reed, a business woman and retired school teacher, and Jamie Harrison, a former S.C. Democratic Party chair and former national Democratic Party, Clyburn said. “I could name 25 people.”

Asked if he was worried the Republican majority in the S.C. General Assembly might try to gerrymander Congressional districts to make it unlikely a Black would be elected to Congress from the state (which is about 25% Black), Clyburn said, “I don’t worry about that. That may happen. But it’s not a worry of mine. It should be a worry of the public. ”

He added, “If we want to see ourselves revert back to post-Civil War, to Jim Crow, that’s not my problem. It’s the country’s problem.”

People praised Clyburn after his talk.

“It is amazing how much progress we’ve made, yet how much more needs to be done,” said Columbia lawyer I.S. Leevy Johnson, who agreed with Clyburn that history is repeating itself and not in a good way for Blacks. “It’s a major concern,” said Johnson, 83, who was one of the first African Americans elected last century to serve in the S.C. Legislature.

Former Columbia Mayor Bob Coble, 72, and his wife of nearly 50 years, Beth, bought a book and were in a long line to have it signed by Clyburn. “Beth and I are honored to be here and hear firsthand that part of history.”

Dante Mozie, 39, who teaches journalism at S.C. State, called the talk “a wonderful event, an important event that tied the past to the present with hopes to improve our future. “

Donaldson, who moderated the event, said, “Jim Clyburn has always been the history teacher, and this book is just one more part of his ongoing educating the public. He said the book was intentionally sobering. It’s also timely. If this book had come out four years ago, the power of the story would not be as captivating.”

©2026 The State. Visit thestate.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC. ©2026 The State. Visit at thestate.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments